In this blog I want to highlight the use of Test.createStub with Force DI, to effectively inject mock implementations of dependent classes. We will go through a small example showing a top-level class with two dependencies. In order to test that class in isolation as part of a true unit test , we will mock its dependencies and then inject the mocks. This blog will also show how Force DI adds value by extracting and encapsulating configuration code from the app.

ChatApp Requirements

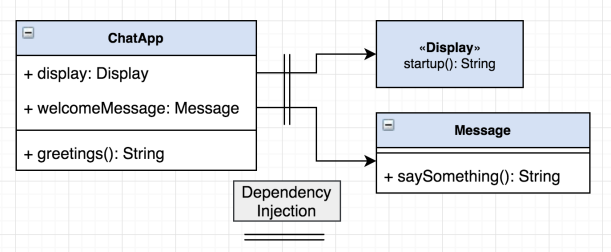

The greeting message for the app should be determined by an out of office setting combined with a configurable initial message. The developers decide to split the concerns of fulfilling this requirement into two classes. An instance of the Display class will handle the system part of the message and an instance of the Message class will be used to obtain the rest. Object orientated programming principles (OOP) have been used to create an interface for Display and base class for Message. The implementations of these are not of huge interest here so are not shown.

Life without Dependency Injection

The following first shows how the ChatApp looks without Dependency Injection.

public class ChatApp {

private Display display;

private Message welcomeMessage;

public ChatApp() {

// Display and Message impls vary based on out of office

if (UserAvailability__c.getInstance().OutOfOffice__c) {

display = new Fun();

welcomeMessage = new Weekend();

} else {

display = new BeAwesome();

welcomeMessage = new Weekday();

}

}

public String greetings() {

// Custom message to greet the user is prefix by the display sentiment

return display.startup() + ':' + welcomeMessage.saySomething();

}

}

As you read through the following Apex test code consider the following:-

- It only directly tests the ChatApp.greetings method but not any of its dependencies.

- To set up the test the developers needed to decide on the configuration approach (custom setting).

- Additionally, implementations of Display and Message had to be coded as well (not shown).

- The developers had to do quite a bit of work to get to the point where they could write the first test.

@IsTest

private static void givenOutOfOfficeOnWeekDayWhenGreetingThenGreatWeekend() {

// Given

UserAvailability__c config = new UserAvailability__c();

config.OutOfOffice__c = true;

insert config;

// When

ChatApp chatApp = new ChatApp();

String greeting = chatApp.greetings();

// Then

System.assertEquals('Party time!:Have a great weelend!', greeting);

}

Now also imagine that the Display class has further dependencies and setup requirements, that would add to the test setup code. It is also not very supportive of Test Driven Development since ChatApp required other dependencies to be implemented for the test to run. Technically it resembles an Integration Test, more than a unit test.

Life with Dependency Injection

The following shows how the ChatApp looks with Dependency Injection.

public class ChatApp {

private Display display =

(Display) di_Injector.Org.getInstance(Display.class);

private Message welcomeMessage =

(Message) di_Injector.Org.getInstance(Message.class);

public String greetings() {

// Custom message to greet the user is prefix by the display sentiment

return display.startup() + ':' + welcomeMessage.saySomething();

}

}

NOTE: It is intentional that there is no reference to any Display and Message Implementations

As you read through the following Apex test code consider the following:-

- It only tests the ChatApp.greetings method code and nothing else.

- Decisions relating to how the configuration would work where not needed.

- Display and Message implementations were not needed.

- As soon as the greetings method was coded a test could be written.

/**

* Unit test for the ChatApp.greetings method with mocked dependencies

**/

@IsTest

private static void givenDisplayAndMessageWhenAppGreatingThenCombinedMessage() {

// Given

ChatAppMockProvider mockProvider = new ChatAppMockProvider();

di_Injector.Org.Bindings.set(new di_Module()

.bind(Message.class).toObject(Test.createStub(Message.class, mockProvider))

.bind(Display.class).toObject(Test.createStub(Display.class, mockProvider)));

// When

ChatApp app = new ChatApp();

String message = app.greetings();

// Then

System.assertEquals('Mock Startup Message:Mock Message', message);

}

/**

* Basic Stub Provider for ChatApp dependencies

**/

private class ChatAppMockProvider implements System.StubProvider {

public Object handleMethodCall(Object stubbedObject, String stubbedMethodName, Type returnType, List listOfParamTypes, List listOfParamNames, List listOfArgs) {

if(stubbedMethodName == 'saySomething') {

return 'Mock Message';

} else if(stubbedMethodName == 'startup') {

return 'Mock Startup Message';

}

return null;

}

}

By using the Force DI di_Injector.Org.Bindings.set method and Test.createStub (read more here) method mock implementations are injected in place of concrete implementations (these need not even exist at this point). This avoids the need to write more code than needed in order to get to a point where a test can be written and run. The use of these two technologies brings the developer experience closer to that of Test Driven Development.

What about Integration Tests?

As I mentioned earlier there was nothing necessarily wrong with the initial test code, its just that in terms of unit testing and TDD, its scope was too broad (it tested more than it needed to). So if we wanted to run this original test now that we have implemented DI above what else is needed?

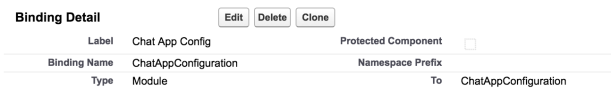

The question you are likely asking is, how do the real (non-mock) implementations of Display and Message get executed? This is where another feature of Force DI comes in. Force DI Modules can be created dynamically per the unit test code above and/or configured via the Binding custom metadata. Once the Binding custom metadata is configured, the following code runs automatically as part of the Injector.Org initialization. Other code defined bindings for DI used elsewhere throughout the app would also go here (read more).

]

]

public class ChatAppConfiguration extends di\_Module {

/**

* Binding configuration for the ChatApp

**/

public override void configure() {

// Display and Message impls vary based on out of office

if (UserAvailability\_\_c.getInstance().OutOfOffice\_\_c) {

bind(Message.class).to(Weekend.class);

bind(Display.class).to(Fun.class);

} else {

bind(Message.class).to(Weekday.class);

bind(Display.class).to(BeAwesome.class);

}

}

}

Below is the original test code we started with, only this time the ChatApp code used the Injector class to resolve its dependencies. Since in production those bindings are not overridden via Injector.Org.Bindings.set method. The Injector code uses the custom metadata based binding configuration, which invokes the module logic above.

private static void givenOutOfOfficeOnWeekDayWhenGreetingThenGreatWeekend() {

// Given

UserAvailability__c config = new UserAvailability__c();

config.OutOfOffice__c = true;

insert config;

// When

ChatApp chatApp = new ChatApp();

String greeting = chatApp.greetings();

// Then

System.assertEquals('Party time!:Have a great weelend!', greeting);

}

Summary

It’s worth pointing out that in wanting to include a configuration requirement in the ChatApp use case the above examples may appear overly complex for basic needs. It can also seem a bit daunting to use OOP concepts like interfaces and base classes for new developers. Well good news! It turns out you can use this approach with regular standalone classes as well. Take a look at the simpler use case below.

public class ChatApp {

// Inject WelcomeMessage

private WelcomeMessage message =

(WelcomeMessage) di_Injector.Org.getInstance(WelcomeMessage.class);

// ...

}

public class ChatAppConfiguration extends di_Module {

public override void configure() {

// Configure binding

bind(WelcomeMessage.class).to(WelcomeMessage.class);

}

}

@IsTest

private static void givenDisplayAndMessageWhenAppGreatingThenCombinedMessage() {

// Inject mock WelcomeMessage

di\_Injector.Org.Bindings.set(new di\_Module()

.bind(WelcomeMessage.class).toObject(

Test.createStub(WelcomeMessage.class, mockWelcomeMessage)));

// ...

}

NOTE: As mentioned in the previous blog, Force DI is based roughly on Java Guice , which also has a great worked example here. The principles explained are the same as here, however, the examples are using annotations to let the Java Guide injector automatically detect where to do the injection. In Force DI, this has to be expressed directly via Injector.Org.getInstance.